AMDG: A Jesuit Podcast

A Conversation About Racism and the Spiritual Exercises

This is a conversation about racism and the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. Put more precisely, this is a conversation about how the Spiritual Exercises might better form us to understand and push back against the repercussions of racism in America.

The question that frames this conversation is one that comes from the global Society of Jesus. At the last General Congregation—GC 36—when Jesuits from around the world gathered to elect a new superior general and examine the most pressing issues facing our world today, this question was raised: Why do the Exercises not change us as deeply as we should hope?

In short, how does injustice and racism and violent persist, even after so many of us have made the Exercises? The Exercises, after all, are meant to change our hearts and minds, to help us better understand God and who God desires that we be with and through community.

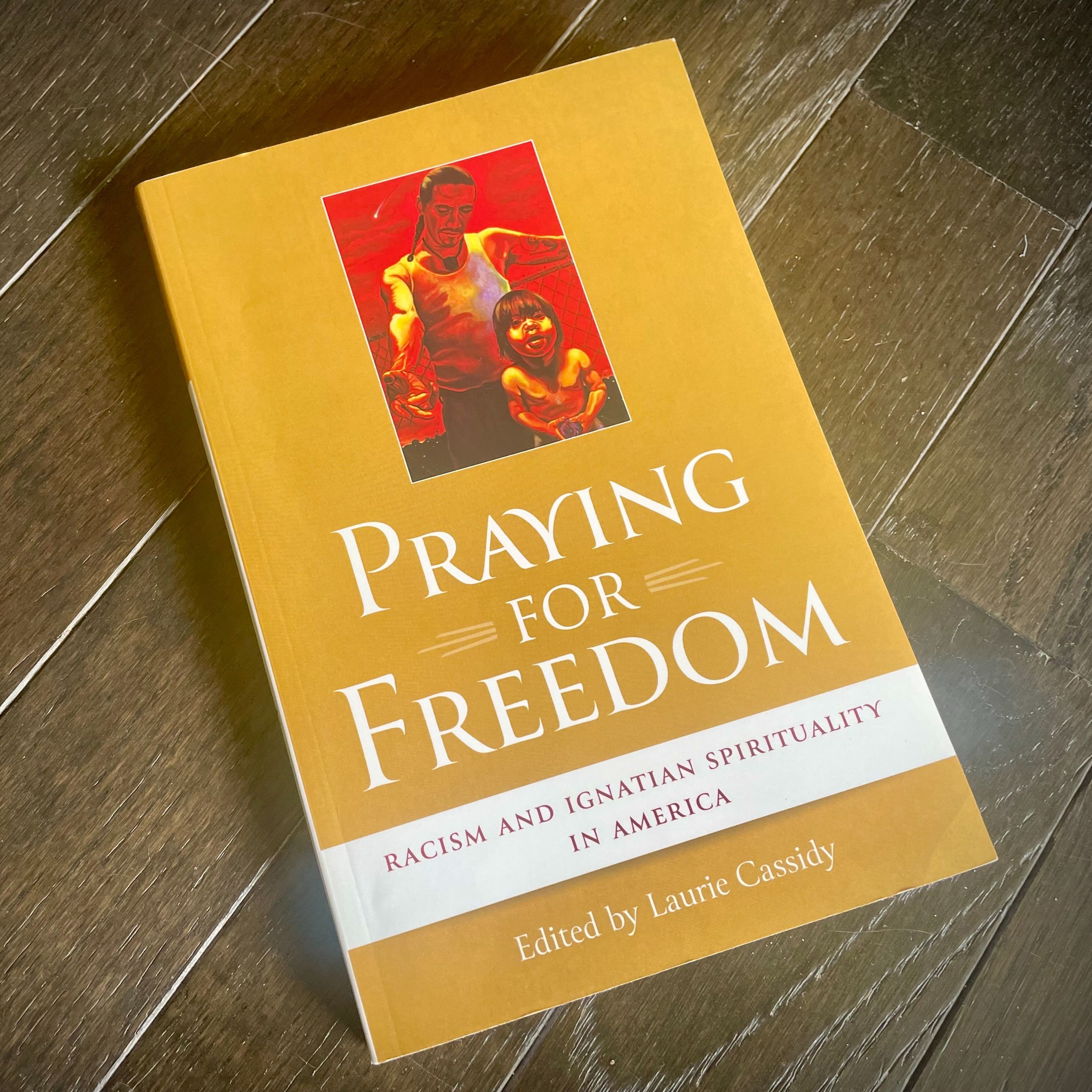

This question is at the heat of a new book from Liturgical Press. It’s called “Praying for Freedom: Racism and Ignatian Spirituality in America.” It’s a collection of essays and reflections that attempt to wrestle with this question and try to envision how we might build a more just and compassionate society.

We have three guests today. Dr. Laurie Cassidy, the editor of the anthology, currently teaches in the Christian Spirituality program at Creighton University. She is an award-winning author and editor, and has been engaged in the ministry of spiritual direction for more than 30 years. Our two other guests, Elise Gower and Justin White, both contributed chapters to this book, both reflecting on their own experiences of a retreat called “The God of Us All: Praying with Black Spirituality.” They both share with us personal and powerful insights into their own prayer life.

Elise has an extensive background in Ignatian spirituality, higher education and leadership, having served as associate director of Contemplative Leaders in Action—a formation program for young adults—and at Loyola University Maryland in the offices of Campus Ministry and the Center for Community Service and Justice, and more. Justin White has a long career in Jesuit education, having taught theology for 8 years at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Baltimore and having held several roles at Loyola Blakefield, most recently as a counselor for middle school students.

If you have ever prayed through the Spiritual Exercises or if that’s something you hope to do, this conversation will add a helpful frame to your prayer and challenge you to examine those places in our lives where we are resistant to God’s love—those places where we are not free.

Our prayer today is one of freedom—as we begin this conversation, let us pray that we all may recognize those places of unfreedom in our lives, and take the necessary steps to step beyond those obstacles.

https://litpress.org/Products/6791/Praying-for-Freedom

- Duration:

- 55m

- Broadcast on:

- 14 Aug 2024

- Audio Format:

- mp3

From the Jesuit Media Lab, this is AMDG, and I'm Eric Clayton. This is a conversation about racism and the spiritual exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. Put more precisely, this is a conversation about how the spiritual exercises might better form us to understand and push back against the repercussions of racism in America. The question that frames this conversation is one that comes from the global society of Jesus. At the last general congregation, GC36, when Jesuits from around the world gathered to elect a new superior general and examine the most pressing issues facing our world today, this question was raised. Why do the exercises not change us as deeply as we should hope? In short, how does injustice and racism and violence persist even after so many of us have made the exercises? The exercises after all are meant to change our hearts and minds, to help us better understand God and who God desires that we become with and through community. This question is at the heart of a really important new book from Liturgical Press. It's called Praying for Freedom, Racism and Ignatian Spirituality in America. It's a collection of essays and reflections that attempt to wrestle with this question and try to envision how we might build a more just and compassionate society. We have three guests today. Dr. Laurie Cassidy, the editor of the anthology, currently teaches in the Christian Spirituality program at Creighton University. She's an award-winning author and editor and has been engaged in the ministry of spiritual direction for more than 30 years. Our two other guests, Elis Gower and Justin White, both contributed chapters to this book, both reflecting on their own experiences of a retreat called "The God of Us All," praying with Black spirituality. They both share with us personal and powerful insights into their own prayer life. Elis has an extensive background in Ignatian spirituality, higher education and leadership, having served as the Associate Director of Contemplative Leaders in Action, a formation program for young adults, and also at Loyola University, Maryland, in the offices of Campus Ministry and the Center for Community Service and Justice. Justin White has a long career in Jesuit education, having taught theology for eight years at Christa Ray Jesuit High School in Baltimore, and having held several roles at Loyola Blakefield. Most recently, as counselor for middle school students. If you have ever prayed through the spiritual exercises, or if that's something you hope to do, this conversation will add a helpful frame to your prayer and challenge you, as it did me, to examine those places in our lives where we are resistant to God's love. Those places where we are not free. Our prayer today is one of freedom. As we begin this conversation, let us pray that we all may recognize those places of unfreedom in our lives and take the necessary steps to move beyond those obstacles. And now, here's Laurie, Justin, and Elis. Elis Justin, Laurie, welcome to AMDG. We're so glad to talk to all of you today about this really important new book, Praying for Freedom, Racism and Ignatian Spirituality in America. So let's just begin, because there's a really key question that kind of frames this entire project. The general congregation, 36, right, GC 36, asks, why don't the spiritual exercises change us as deeply as we should hope, right? So I want you to tell us a little bit about this question and its answers, and why they're so pivotal to this moment in our church and in our country. Laurie, why don't you start us off? Sure. I'd be happy to. I just really want to thank Lucas Sharma, SJ, for introducing me to this question, because it's such a prayer provoking question. And there's so many ways of exploring this in relationship to racism. I just want to take one piece of it. Yeah. Why are there so many books on the exercises in America? And it's still really hard for white people to address our being white. And why are we not curious about white nationalism? Which Brian Masigill says is one of the most serious problems that we have to face in America right now. And that's thought provoking to me and extremely disturbing. I think the question and the wording of the question itself is really, really powerful, because the question could be, how can the spiritual exercises bring us to a deeper understanding of hope and challenges, but that notion of why doesn't it, I think, does provoke that prayer and that deep discernment and really causes you to grapple with the answer of that. And so I won't speak for the Society of Jesus, but I know when I went through the 19th annotation of the spiritual exercises, and I was in my last year of graduate school as well. So I was being formed in so many different ways. And when I came out of the program, you know, quote unquote exit the program because it stays with you forever, I just felt a deeper sense of expansion when it came to my own understanding of God's love for me, but then also expansion for God's love for all of creation. And I think maybe, you know, that expansion involves work too, you know, at least you talked about in your piece, like you create the newness and expansion as you were coming out of the retreat, but newness and expansion does cause you to look at what you got going on in your own life, look at what you got going on and the things that you're connected with and think about, all right, where does the work, you know, those capital letter work that Dr. Marine talks about, you know, that that's challenging. That's challenging to do. And so I wonder there's deepness involved, but there's also expansion and expansion should and could challenge, but maybe that challenge is scary to folks. Maybe that challenge is looked at without really consulting the spirit and recognizing that the good news is going to help us with that. Maybe there's some fear and doubt and really understanding like how expansive we can actually get and be I'm so grateful for both of you and what you already shared and I'm just sitting with and I'm really drawn to this sort of distinction that you offer Justin in saying, well, we can ask, you know, how can the spiritual exercises change us deeply, right? But the question we're posed with was why don't the spiritual exercises and for me, that sort of comes up against that idea of expansion when we think of it in the signs of the times. And so I've been thinking a lot about I've been reading this book, The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Heit, and thinking about the ways in which we're a society that is so screen-based. And I actually think that the spiritual exercises require this authentic freedom and detachment that I just don't think our society has right now, right? We're so attached, we're attached to false narratives that are just constantly inundating us in our news and our social media and so to detach from that, we have to be inundated by God and I don't know that we take the time and the space or find the time and space to do that in a way that really has us examine our histories and to recognize our responsibilities personally and communally and, you know, Brother Ken Holmes talks a lot about that in his section. At least the way you just said that, the both of you just helped me a lot because I think the question, why doesn't it? It's because I think spirituality in many cases becomes a way of dealing with how overwhelmed people are. It becomes domesticated in terms of, oh, helping me deal with my anxiety, helping me deal with my depression. It becomes domesticated in how it becomes self-help in contrast to the expansive consciousness that you folks are talking about. That to me sounds like it's reactive as well and I don't know if there's expansiveness in reaction. Let's talk about freedom because at least you mentioned freedom. Obviously, freedom is in the title of the book and freedom is foundational to the Ignatian tradition. You know in your introduction, "Freedom conjures deeply contested visions and contradictory realities that are imprinted upon our national psyche." Then you go on to say, "Seeing the face of God in our lives may not only involve freedom from distorted images from our own personal histories, but also freedom from the distorted narrative narratives of white supremacy." How do we begin then to better understand and grapple with the kind of freedom that God desires for us in this way that you all have been describing? Justin, do you want to start us off? Yeah, it is an expansive question, so I appreciate that question in a lot of different ways. I think where my mind and heart landed on coming up with some kind of contribution to it is I think it begins with really examining our personal and our collective truths. I think part of that involves some unearthing of things, some excavation, Brother Homan really talks about that he was on that dig with the descendants, really not only working with the materials but also digging within himself to understand what is my response to this. I think one of the ways in which we can find where we need the dig is look at where we're uncomfortable. Let's speak to reality that the reality of white supremacy, just hearing that, makes people uncomfortable in a lot of different ways and I don't think there's anything wrong with that uncomfortability but it's unhelpful if that feeling of uncomfort leads to dismissiveness, leads to denial, leads to more bias, leads to hatred, leads to violence, leads to death. That's when that uncomfortable feeling is not helpful to the kingdom of God. So when we had that uncomfortable feeling, where is that coming from? I got to dig into that. But in my own personal history is connected to that and what in the collective truth and history is connected to that and once we start to grapple with that, I think it does lead to greater freedom because then we have choice. Once we have some knowledge, we have choice of what we want to do with it and once again, sometimes that choice is scary because the choice then means that I can hold myself accountable and those who I'm in community with can hold me accountable too. I think a piece that I would add is how intermingled our freedom is and as a society and white nationalism and white supremacy, white culture does not see whiteness as connected to all of humanity and people of color and black and brown bodies. And so, for me, this idea of freedom has to be, you know, it's talked about this idea in flesh, exploring freedom on multiple levels. How do I explore my freedom as intrinsically connected to another person's freedom? And until I do that, I'm not really free. Yeah, there's so much to this because I'm going back to texts that I read when I first started experiencing the exercises. Freedom from what? And freedom for what? And just in a very practical way, you know, how do the exercises make me free from fear to be able to ask certain kinds of questions? For example, you know, am I afraid if somebody asks me about being white? Am I afraid if the very word white comes up? And can I be free to be curious about my experience? I think that's the thing that is troubling to me is that for Catholics who are involved in horror white, who are involved in the exercises, do we have curiosity about who we are and how other people see us? And do we have a fearlessness to be able to engage in conversations about who we are? Are we free to explore that? And that's on a very fundamental level. I'd like to hear you all talking about curiosity and Justin, you give us that good image, you know, based in Brother Ken's essay for this collection, but of the excavation, which I think is helpful. And I like the idea of you have to get, you have to look at yourself pretty plainly and realistically and then hold up that knowledge, like you said, to the light so you could act upon it. I think that's a really helpful way of thinking about it. Once you discover something, then you have this ability to act on that. And so, throughout all of this text, this emphasis on specificity and particularity, really sinking into a place, a history, circumstances, the land, it all informs our memory, both for good and for bad. So I wonder, just for all of you, how does this Ignatian idea of grace history really help us to sink into our own particularity as we seek this radical transformation by God for God's work? Two things come to mind. One is, I'm kind of playing with the term intimacy, right? And I think about relationships and the ways in which I'm intimate in those relationships. And intimacy will take different shape based on who I'm in relationship with. When they think about being in relationship with God, it's got to mandate that I'm intimate with myself. And I often find that when I'm not intimate with myself, then that is projected in my relationship with God. So understanding the particularities of who I am and the specificities of God's creation in me is the only way that I can truly be intimate with God on a level beyond self, right? And also pertaining to myself, I think about one of the things that Marilyn Nash wrote, which I just have spent a lot of time with, you know, she said, quote, burdening Ignatius with understanding racism in the US in the 21st century is unreasonable. Yet we are called to observe the signs of the times, end quote. And so I just think St. Ignatius, his initial vision was constantly evolving and adapting based on the specifications of the time and so how are we called to have that evolution as well in self and in community with others? Yeah, that constantly evolving, right? And there should be excitement and joy with that as well as, you know, challenge and discernment as well too, you know, God has been actively acting, you know, God has been and still is. And I think when we talk about that grace history, it's an invitation to look at our own personal ways of being, look at our collective ways of being and asking ourselves, and what ways have we worked with that grace and what ways have we worked against that grace? And when we do that, once again, we can act out of freedom to say, okay, I want to work. I want to continue to work in that grace. So that constantly evolving makes absolute sense to me. And from where I'm seated, I really look at spirituality in psychology now as a counselor. And I just think about when we look at the psychology feel like how much research that existed, do we have folks, you know, debunking or saying that there wasn't correct because of the way it was done, the place and the time, the matter which is done, folks adding on to it, like that's important, right? That's important to continue. Look at the signs of the times, understand how can we increase the quality of life for those around us from a metaphysical, mental, emotional, spiritual way? And I think that that's a beautiful invitation. And I think that's part of the work as well too. This whole notion of grace history is constantly plaguing me because I think to myself, hmm, how do I really understand my history? I think I've seen my history as very personal, you know, my family where I grew up and then putting the frame and beginning to understand my history as a part of a bigger history. And when we talk about salvation history, that can be very abstract, but what about the salvation history of in my place in Holliston, Massachusetts, where I grew up, taking my family and putting it in the context of the land that I grew up on, the history of Holliston, my Irish ancestors, because situating my history, in real history, in the bigger history, is actually a way of beginning to see God, a bigger history of God and God's face in my life, not just in my personal history, but situating it in a larger context. What I hear from each of you is, and I think you've said it, is this excitement to engage with this history. And I think, you know, I like, at least where you started with this idea of intimacy, intimacy with self, because there's a, there's a quote I go back to a lot by Tara Desjardins, and I'm not going to be able to remember it. But essentially, there's this constant unfolding of self that we are an endless mystery in which we can enter into and encounter God. And I think that's exciting. But then that excitement as we, as we engage with things that we, what we're talking about is hard, right? But when we engage with it, with that curiosity and excitement and that trust that, hey, like, good things can come from doing this hard stuff. I think that really changes, changes kind of how people would otherwise approach it. And yet, you use, I think, Laurie, it was you and your introduction again, this, you know, kind of quote, that we're invited to contemplate the past school mystery unfolding on this land, which is not necessarily really like, hooray, kind of a frame, right? Because because that's necessarily hard and challenging and makes us look at stuff in our own self, in our own grace history, that is uncomfortable, as you said, Justin, right? And yet, we aren't called to be paralyzed by that. And so for each of you, what is, what is that, that invitation to contemplate the past school mystery on this land, demand of you or how does it resonate in your own life and work? That's a huge question and a wonderful one. I, I think what, when we see the past school mystery is like noticing God alive in the dynamic of Christ's life being embodied in us. And I think what I'm beginning to discover is when I look at my own family history in light of America and American history, I start to find the resurrection, not just the cross. Like when I started to uncover my own Irish heritage, I began to discover our complicity and whiteness and also sources of resistance to that resources I didn't even know about. So for me, it was discovering this web of life and death and God's grace in the midst of that bringing new life in ways that I could not see before. And I think that's, that's one of the things for me as a white person is that I'm discovering the face of God in ways that I could not imagine if I only looked at just myself and only saw spirituality as something about self improvement. It's like that I was invited out into the kingdom of God, not just about being a better person. Does that resonate with you, Elise, and Justin, like how do you see this? It really resonates. I've been in the midst of my own excavation most recently and probably embodiment, right? In my white body, not just contemplating the Paschal mystery, but participating in the Paschal mystery and consciously participating. I am temporarily living in my hometown of Whitehaven, Pennsylvania, a small square mile town whose title gives you an image of where I'm from and I have spent so much time burying, not excavating, but burying that piece of my history. And so when I moved to Baltimore, where I've proudly called home for almost 15 years of predominantly Black City, I just let go of that history. I buried it further and only found joy in the presence of the demographics of Baltimore and the community of Baltimore. And now that I'm home, I'm faced with all that I have not excavated. And I've been thinking about Jesus, the life and embodiment of Jesus. And Jesus did not just hang with people who thought like he did, right? That is not the story of the gospels. And so I'm confronted with not just putting down the people of my community who have not had the experiences, the education, the exposure, the communal relationships that I've been blessed with, but to be in relationship with them too, right? And so right now living the Paschal mystery is engaging in the suffering of my local town and also articulating a message of resurrection that I believe in that might be counter to others' beliefs in this area. But that engages us in a human encounter that can allow for some type of transformation to occur. That human encounter, when I was doing the exercises, there was at one part during my prayer and my discernment and contemplation where I was having trouble picturing Jesus, like physically picturing Jesus, because I was really struggling with all of the depictions that I had had in Jesus up to that point. And so at that time, you know, I think I'm 33 or 34, I'm wrestling with this history of all these depictions I came. And I was like, I want to, I want to get to know the Jesus. I want to be of Jesus. But I need some, like I need it to resonate with me a little bit more. And so it was very beautiful. So the image of Jesus, Chadwick Boseman, became my image of Jesus. And that's not, you know, placing Chadwick Boseman on, you know, an idle level or anything like that, because he was human as well, too, and he suffered as well, too. But in that envisioning and embodying of Jesus, I was able to connect more and Jesus became my brother, Jesus became someone I dapped up, Jesus became someone I sat with at the fire while he was cooking the fish and things like that. So when we got to the third week of the exercises and Jesus is suffering, I felt that. Like I felt it, I felt the sadness, I felt the anger, I felt all of that. So for me, the Pascal mystery really invites us to wrestle with needless suffering. Yes, Jesus died and fulfilled in a scripture and part of God's will. Yes, Jesus really chose that death. Yes, Jesus conquered death. But I think it's our job to conquer, alleviate needless suffering and needless is important because suffering exists in the world, but there's some needless suffering that doesn't need to exist. So when I think about the Pascal mystery, my heart and my mind goes to that. I remember in middle school, when I learned about crucifixion, I was like disturbed. I was disturbed. Like this is how we punish people that like I was completely disturbed and, you know, it was presented as like, yeah, that's how criminals and people were punished. Why? Why? And so that why I think still needs to be asked today when we think about the needless suffering that so many people go through in this world is an invitation to look at how can we take the joy of the resurrection? How can we take the notion that death has been conquered and apply it to the needless suffering that exists? Each of you has done such a really great job of bringing us into your own prayer, which I think is so key to an authentic experience of the exercises and I think for folks that are listening who have gone through the exercises or who may be interested in it, like this idea, like this is that like making it our bringing into our own reality is so key for that transformation that we're after. I have another quote from the introduction and I know it sounds like I'm like trying to do like a term paper here or prove that I did the reading, but these are all quotes that really, really struck me. And so this is the quote, colorblind racism impacts our interpretation of the spiritual exercises, like a pair of reading glasses, end quote. Let's hear some reactions to that sentiment. I think it's really important and it hit me and it kind of really challenged me to go back and think, oh, how and more importantly, like what grows from or kind of what weeds perhaps grow from that kind of a starting place. Okay, so a few things are simmering, one, I am a person who wears glasses, right? Every year I have to change my prescription because every year I can't see out of last years and so this idea that it's like a pair of reading glasses is so true and yet it negates that take the glasses off, put a new pair on, right? Ask people how they're seeing something. That's just a limited visual that I offer. More so I go back to what I already named that Marilyn Nash offered, which was to suggest that St. Ignatius could have grappled with racism in the 21st century, right? It is not a thing and so we have to look at what the exercises tell us and the exercises tell us as Marilyn says, the exercises are not neutral, they're not meant to be neutral and yet that's how we often spiritual directors retreats, right? That is often how the exercises are presented as to be neutral to the person moving through the exercises. And Marilyn challenges the gospel and life of Jesus are certainly not neutral, right? So there has to be an element of discernment. It's not just putting on the glasses or taking the glasses off but discerning what we see, discerning what we feel, discerning what we hear. Yeah, if you say you love me or you say you want to love me, you got to see me and you got to be committed to understanding me and you got to see all of me and you got to be willing to try to understand all of me. So in an attempt to potentially stay away from the uncomfortable in an attempt to potentially position ourselves of how of reality when someone enters a colorblind mindset, you're missing a whole bunch and when you're doing it, you're not living in that expansiveness, that expansion if that once again is going to challenge you. But that expansive that's going to allow you to see joy as well too. Yeah, so going back to at least talk about that intimacy, right? It's the intimate, you got to see, you got to see, you got to hear, you got to want to hear anything that's blocking that. I think we're invited to really, once again, the word grapple keeps coming around my eyes. I think that's really what it is. All of us are invited to grapple with that. I just want to add one thing to what you're saying, Justin, when you talk about expansiveness, I think about the first principle in foundation and the concept of abundance, right? And those glasses, the colorblind glasses are from this place of fear and scarcity. So to see a person fully is that expansive abundance of God. And if I'm not willing to see color, right? If I'm not willing to see the fullness of a person, then I'm not willing to experience the fullness of God. Absolutely. Lori, I believe you wrote those words that we're quoting. So perhaps you can share some thoughts on what you were thinking. First, we're always interpreting the exercises, which is to say, you know, you can pretend that, okay, we need to go by the text. I really want to make the exercises, right? But you're always going to be interpreting what that experience is. I remember hearing this amazing talk by Howard Gray. He was talking about how spiritual directors help people in the fourth week. And he said, you know, you really have to have some things in the back of your mind. You have to have ways of understanding scripture. You don't tell the direct D that, but you always have it in the back of your mind. And to me, that's powerful because he's demonstrating, we're always interpreting. We always have a frame of reference in the back of our mind, right? And so that's always happening when a director is directing the exercises or when we're even reading about the exercises. But you know, for me, I never noticed that I was a white person and I had things that I understood that were what the exercises were about and that I was actually taught all the other things like even social justice issues shouldn't really come into the long retreat. You shouldn't bring up anything because that's kind of interfering with what God should be doing. And I think we have to explore that as spiritual directors because there's all these assumptions that we bring all the time to our conversations. We're just not aware of them. And I think Elise demonstrated that in her essay because by going to the retreat that she went to with Justin, she began to uncover the assumptions that she had had about God that she wasn't aware of. Am I right about that, Elise? Yes. Well, that's a great pivot point. I want to let's talk about Justin and Elise, both of your essays because they're both based in this experience of these retreats, the God of us all praying with Black spirituality. So maybe one of both of you can kind of give us just what is this retreat about? What was this retreat about? Where did it come from? How does it respond? What we've been discussing? And then we'll get into each of your essays. So Justin, why don't you take it away? Absolutely. So the God of us all praying with Black spirituality, it's the fruit of the jars collective and jars is the Jesuit anti-racism, so dality, meaning a group or fellowship of folks working towards a cause and this cause is furthering the mission of anti-racism in our church. And so you had Jesuits information, Jesuits ordained and lay folk coming together to make this experience of diving deeper into freedom through using the Ignatian orientation to lift up and center Black spirituality. And that was in collaboration with our Black Jesuits and Black theologians and professors. And so using that Ignatian orientation once again to lift up and center Black spirituality, you can't talk about freedom if I'll talk about Black spirituality because Black spirituality is talking about freedom in all of its essence, mentally, physically, spiritually, metaphysically. And so the retreat through the sacred songs, the Black spirituals, through ancestors that are part of the communion of saints and those folks that are still working here on earth for the kingdom of God and through the witness from our spiritual directors, everyone was invited into this deeper sense of freedom by understanding and journeying with Black spirituality. Awesome. There's a new frame here chapter with a really poignant quote from Sister Thea Bowman, "I come to my church fully functioning. I come to my church fully functioning. Can you share with us a little bit why that resonates with you and why you wanted to start this, your whole chapter with that piece." Yeah, I want to first shout out my eighth great teacher, Mrs. Bonner, because I think she, if I'm not mistaken, she exposed us to Sister Thea Bowman. She exposed us so many Jesuit things, St. Oscar Romero. And as an eighth grader, I might not have been so in tune at that time, but I think the spirit was planting some seeds at that time that have really began the blossom. And so I had never fully watched the, I'm not even calling it a speech, the witness of Sister Thea Bowman in front of all of the Catholic bishops and folks listening or watching, if you haven't watched that address, please, please watch that address. If you watch it in the past and you haven't watched it recently, watch it, you know, it's going to do your soul a lot of good because what you witness is a woman fully, fully alive and operating out of joy. And over these three years of being part of the retreat, Sister Thea Bowman has always been one of our ancestors. And I feel like I've just gotten to know her more, especially when you have, you know, Father Joseph Brown, shout out to him, who was a friend of Sister Thea Bowman, who was a colleague, who traveled with her, worked with her, gave lectures with her, learned alongside her, to have him witness to her power, her strength, her joy. I just feel like she's an ancestor that's very close to me and I've envisioned seeing her and being in awe and her just coming up and hugging me and being like, "Baby, how you doing?" You know, just very intimate, going back to that. And so that notion of fully functioning, you know, what does it look like when we come before God without the fear, without the doubts and without the shame? What does it look like to come before God and fully be ourselves? And as people of color, as people who have identities that have been marginalized, unfortunately institutions and those within the institutions have been the people to give the fear that doubt and the shame. So what does it look like when we make a commitment to say that you are fearfully and wonderfully made in every sense of the word and anything that says contrary to that, like we're not about that, because we want you to show up as fully as possible, because when you show up fully as possible, joy is going to come out. And one of my favorite things about the whole entire witness is, I'm not going to sit here and assume that I know what's going through the Bishop's brain, that would be silly. But when the camera pans to the bishops in the audience, you know, you see people wiping away tears, you see people fully smiling, you see people with a really discerned look on their face, and I can't just help but think like the amount of healing that was happening in that space, and how then those leaders of the church, for the church, but in their own lives as well, how are they going to bring that to other folks? Because they're witnessing a woman fully and completely alive and joyous. That is only going to animate you. That's only going to animate you, or you have an invitation to be animated. So that notion of fully function, I didn't know that that was going to resonate with me as much. And I also didn't know that I wasn't fully functioning. And when my really good friend, Father Sean Tua, invited me on the retreat, and I wrote about this in the essay, I hesitated because I was fearful, I was doubtful. I didn't want to enter a space that I thought was going to be performative, right? This is 2021. We're coming out of the summer of 2022, like I was hurting. I was hurting really, really bad, and I didn't want to enter that space and being the good friend that he is, he heard me, he validated me, and he responded back with, you're not going there to be a PLC evaluator, you're just going there to be with God, and that's what happened. And I experienced a great deal of healing and community there. And I came out, I want to say closer to fully function, the journey continues, but I became closer to it. So yeah. Beautiful. You also write, when a space for true racial reconciliation is granted, healing in other areas of one's life can appear. I think you just described that so beautifully, but I love that quote, I wanted to read it aloud. I think you can share kind of, again, other from your own experience or kind of that you want the listeners to walk away with that helps us to better understand how integrating and understanding our full selves can bring that true racial reconciliation. Yeah, it connects to everything that we've been talking about. When I'm in a space and I feel like people are making a commitment to see me, when folks are making a commitment to try to understand my perspective, and people have made a commitment to understand that I've been disproportionately harmed by society and white supremacy. I have invitation to show up a little bit more fuller, right? When, you know, once again, when you're a person of a marginalized identity, and Patrick St. John talks about this, your body often feels unsafe. So I'm constantly going into physical spaces, virtual spaces, and I'm checking out the scene, right? Dr. Matthew talked about that, right? He asked him what his job was, and he says, "I teach African-American religion and Catholicism," and he received a hostile response simply from saying that's what he taught from a deacon. And so when folks make a commitment, right, that anti-racist commitment, once again, to say that I'm going to see the folks in the room, I'm going to try to understand the perspective, but I'm also going to recognize that there's been disproportionate harm. I think folks are able to be more vulnerable. And so what I saw is I saw people talking about their relationships, which as we were talking about their vocations, people were talking about their family members. And it wasn't like, oh, no, I don't want to talk about race and racial justice. It was, okay, because we are recognizing there's really immense, painful history. Because we're wrestling with our humanity, then I'm able to talk about the other parts of my humanity as well. And that's what reconciliation is, right, relationship, reconciling my relationship with myself, reconciling my relationship with God, and reconciling my relationship with others. Beautiful. Thank you. At least in your chapter, then you kind of pick up on some of these same themes. You write, "Graditude emerged from my ability to be spiritually whole in my whiteness, not despite it." Can you talk a little bit about how that experience fits into this larger work of praying for freedom? Yes, and I want to go back to something that Justin said, "I didn't even know I wasn't fully functioning," right? That just really resonates with my own writing and my own prayer life. So I've participated in a lot of racial justice initiatives and anti-racism trainings. And so I felt really ready for this retreat, and you can't see my colleagues laughing because they know I wasn't, because this retreat revealed some really unexplored ideas that I've held subconsciously. I can say intellectually that I understand being white is not a sin, right? But spiritually, I've really misconstrued this, and I've allowed my whiteness to be a block to understanding God's creation in me. In 2023, I participated in the Ignatian spirituality and anti-racism gathering in Arizona, and Lori Stanley, the executive director of the Loyola Institute for Spirituality, she spoke about the exercises. And she quoted Patrick St. John in saying, "racism is the sin of division." And I was having a conversation with a friend that night, and she put it so simply. She said, "Sin is a block to God." And racism is the block to receiving the fullness of God's love in and through one another. So I've thought a lot about that, and the first week of the exercises is about acknowledging that we're sinners, right? The block of racism rooted in systems and structures that oppress, that internalize messages and exacerbate power, and the ways in which it blocks our ability to show up to God's love is our personal encounter with racism. So my dad has a saying for it. He always says, "Love out of your sin." So if we were in trouble, right, and we went to blame our siblings, he'd say, "No, no. You have to love them harder. You have to love them more. You did this to your brother. Now you have to love him more." And he would emphasize this in saying, "We can't just be sorry. We have to learn from it." And in the first week of the exercises, that's what the first principle of a foundation is, right? It's our calling, our response to God's love. And Fred Gomeno writes about this on IgnatiansBirituality.com, and he says, "The deepening of God's life goes back to our goal to love and be in love. God is love." And so when I go back to the first principle and foundation, I learned later that St. Ignatius didn't even intend for the first principle and foundation to be there. He had to add it. And I love that because he realized that not every retreatant was arriving at the first principle, or I'm sorry, the first week of the exercises, already aware of God's love. And so instead they were getting stuck on their sin, right? They were spiraling in shame and not being able to navigate guilt in a way that fosters real healing. And that moves us further from freedom and openness, further from receiving God's unconditional love. So the gratitude that I hold is that I discovered my prayer around sin has to be connected to our call in Christ. And I'm a queer Catholic, and for a long time I've fought the narrative that God loves me despite my queer identity, right? To be fully functioning means to be fully functioning in my queer being. But I also need to fight the narrative that God loves me despite my whiteness. God loves me in my whiteness, in my goodness, in my response to God's love, and as a beloved sinner who's benefiting from white supremacy. And until I can realize that, I'm not sure true transformation can occur. Thank you. Thank you. At least you also write, and you touched on this a little bit here just now, but there's this need to de-center ourselves in prayer right before God. And I wonder, you know, I wonder, as we do what you just described, like God loves us because of our fullness of self, how do we then de-center ourselves to allow God to more fully work through us, right? How do we hold both of these things in our, in our prayer and on like prayer and daily life, not just, you know, when we go on retreat? Yeah, I would offer this question to all of you, but at least I think you're the one who touched on it in your chapter. So you got to answer first, sorry. Well, I'll tell you, Justin sort of already answered it earlier in, in, for me in talking about this idea of needing to resonate with and see Jesus in a new and different way. So I thought a lot about this in writing my essay, but I've actually been thinking a lot more about it since it's been published because I, I'm not sure I captured something accurately, right? And I haven't actually held white images of God. I can say that because for a long time I've, I've moved beyond the human confines of race and gender to understand the divine, but I'm getting stuck in the person of Jesus. I've spent a long time unlearning and releasing false images that I've been raised with. You know, we know Jesus was not light and yet I'm not sure I've become intimate with a black Jesus or a brown Jesus. And this retreat, it created a place in which I was arriving to a Jesus reflecting the diverse community that I was, I was praying with. I no longer had to imagine or create Jesus as a person of color. I was discovering him and I was being loved by him and I was learning about him and the history that are of our country, right? Through the spirituals, I was learning all of these things in the song and I was feeling him for the first time in my body and I would say Elise finally got out of the way. I think Elise's words are so powerful and I think she's demonstrating we don't decent her. God does. And we discover what that experience is. And I think just want to, I'm so resonating with all of this about the first week because in terms of being a loved sinner and discovering that in relationship to my white identity. James Baldwin has this amazing quotation. If white people loved themselves, there would be no racism. Oh my goodness. Oh my goodness, oh my goodness. I mean, can you, that to me is so profound in relationship to the first week. Because it's saying, wow, if we can bring our whole selves to the first week, then the first week has a way of subverting white supremacy. I mean, that to me is really profound because it's saying you don't have to do the exercises to become a good white person. No, it's about allowing ourselves to more fully show up as our whole self and discovering who God is in that place, becoming more free and I have to say, you know, Eric, you know, Jim Bolar, may he rest in peace, this wonderful Jesuit, Jim Bolar, Jim used to say, you know, the more real we can be with God, the more real God can be with us. And so I think that the more we can show up as our fully functioning selves, the more we can understand how as even as white people, we have been blind to who we are, the more we can create conditions for God's love to come into those places that maybe we don't even know about yet. Going back to that last question, I think decentering and being decentered is a sign of freedom because we aren't holding on to whatever notion that we thought we needed to have to exist in life. And when we and our locus of control decide to the center, right, we're lifting up other folks and those are not building the kingdom. The gaze of my heart is on young people. Young people just really want to be seen, heard and understood. And so that's where I that's where my heart is. I hope that young people are able to experience deeper levels of freedom. I hope we as the grownups recognize our role in helping them do that because they are seeing and they're hearing and they're trying to understand the world around them. And so my prayer and my hope is that we as the grownups are able to experience deeper levels of freedom so we can help our young people experience that as well too. Boy, one of the things I just noticed about this conversation is there's so much to what we're talking about. And that was one of the desires I had from the book that it that there can be more public collective conversations about the exercises in America today related to systems of oppression. And I want to just go back to the question we asked at the beginning of our conversation about, you know, why don't the exercises change us more? And I wonder if it's because in one way, we don't ask people of color what they expect from us after making the exercises. You know, it would be really interesting just, you know, Justin, if I were to go make a 30 day retreat, what would you really want from me after making that 30 day retreat? You know, what kind of relationship would you want with me? What kind of freedom would you desire in our conversations? How do we become accountable to people who don't look like us after making the exercises? And how would that change some of our desires when we participate in the dynamic of the exercises? Even just hearing that just kind of it makes me emotional because it's not about being good. It's not about being bad. It's not about trying to check a box. It's not trying to a soldier guilt like I hear and that is like a desire for love and a desire to be in relationship. And I think that's what we need. That's what we need. Thank you for not just this conversation, but Lori for the invitation to be a part of this book. A fun note, Lori was my professor in my undergrad studies at Marywood University and I took a lot of Lori's classes because I loved her so much. And we have remained in relationship and the thing that has been consistent has been the thing I feared the most in her classroom. And it was when she said, "Oh, could you tell me more about that?" Because then you had to own what you said, right? And you had to think more deeply and you had to engage the idea that you just put out to your peers. And that's exactly how my being a part of this book came about because I was just telling her about the retreat and she said, "Could you say more about that?" And I think Justin would agree that having to write, getting to write this essay requires the exercises to continue into today and onto the paper. And my hope for everyone is that they can find relationships like I have with Justin and Lori who are conversation partners, who invite me deeper, who challenge me in the places I haven't reached a depth, and who are a safe place for these conversations of transformation to occur, and that's really counter to, I think, society and the way in which we don't even know how to dialogue anymore. Well, I want to say thank you to all three of you, at least Justin and Lori. This has been a really poignant conversation just to be a part of and to listen to. And I want to thank you for your book. Again, Praying for Freedom, Racism, and Ignatian Spiritality in America is now available from a liturgical press, and I imagine anywhere you get your books from, we will include some links in the notes to this episode. Thank you for being here. Well be well. AMDG is a production of the Jesuit Media Lab, a project of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States in Washington DC. This episode was edited by me, Eric Clayton. Our theme music is by Kevin Lasky. The Jesuit Conference Communications Team is Marcus Bleach, Michael Lasky, Megan Leepch, Becky Sindelar, and me, Eric Clayton. Connect with the Jesuits online at Jesuits.org, on X at @ JesuitNews, on Instagram at @wearethejesuits and on Facebook at facebook.com/jesuits. You can also sign up for our weekly email series, now to discern this, by visiting Jesuits.org/weekly. The Jesuit Media Lab offers courses and resources at the intersection of Ignatian Spirituality and Creativity. If you're a writer, podcaster, filmmaker, visual artist, or other creator, check out our offerings at jesuitmedialab.org. If you or someone you know might be called to discern a vocation to the Jesuits, connect with a Jesuit vocation promoter at bijesuit.org. Drop us an email with questions or comments at media@jesuits.org. You can subscribe to the show on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And as St. Ignatius of Loyola, may or may not have said, go and set the world on fire. [Music] (chimes) [BLANK_AUDIO]

This is a conversation about racism and the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. Put more precisely, this is a conversation about how the Spiritual Exercises might better form us to understand and push back against the repercussions of racism in America.

The question that frames this conversation is one that comes from the global Society of Jesus. At the last General Congregation—GC 36—when Jesuits from around the world gathered to elect a new superior general and examine the most pressing issues facing our world today, this question was raised: Why do the Exercises not change us as deeply as we should hope?

In short, how does injustice and racism and violent persist, even after so many of us have made the Exercises? The Exercises, after all, are meant to change our hearts and minds, to help us better understand God and who God desires that we be with and through community.

This question is at the heat of a new book from Liturgical Press. It’s called “Praying for Freedom: Racism and Ignatian Spirituality in America.” It’s a collection of essays and reflections that attempt to wrestle with this question and try to envision how we might build a more just and compassionate society.

We have three guests today. Dr. Laurie Cassidy, the editor of the anthology, currently teaches in the Christian Spirituality program at Creighton University. She is an award-winning author and editor, and has been engaged in the ministry of spiritual direction for more than 30 years. Our two other guests, Elise Gower and Justin White, both contributed chapters to this book, both reflecting on their own experiences of a retreat called “The God of Us All: Praying with Black Spirituality.” They both share with us personal and powerful insights into their own prayer life.

Elise has an extensive background in Ignatian spirituality, higher education and leadership, having served as associate director of Contemplative Leaders in Action—a formation program for young adults—and at Loyola University Maryland in the offices of Campus Ministry and the Center for Community Service and Justice, and more. Justin White has a long career in Jesuit education, having taught theology for 8 years at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Baltimore and having held several roles at Loyola Blakefield, most recently as a counselor for middle school students.

If you have ever prayed through the Spiritual Exercises or if that’s something you hope to do, this conversation will add a helpful frame to your prayer and challenge you to examine those places in our lives where we are resistant to God’s love—those places where we are not free.

Our prayer today is one of freedom—as we begin this conversation, let us pray that we all may recognize those places of unfreedom in our lives, and take the necessary steps to step beyond those obstacles.

https://litpress.org/Products/6791/Praying-for-Freedom